Takao Ozawa and his contribution to America

Ozawa v. the United States is a narration about immigration of the Japanese populace to America. A major “pull” element for Japanese immigration to America in the late 1860s was the shortage of labor produced by growing aggression among white Californians toward immigrants from China. This hostility ended in 1882 after the endorsement of the Exclusion Act, which forbade Chinese migration and naturalization. A major “push” element was the political, economic, and legal reforms of Japan. In the 1880s, Japan upturned its non-emigration policy and geopolitical seclusion as a part of this reform. In addition, the Japanese administration publicized laws designed to eliminate out-of-date lords from their lands; consequently, a large proportion of Japanese agrarian laborers were forced out of plots that they had tended for a long time.

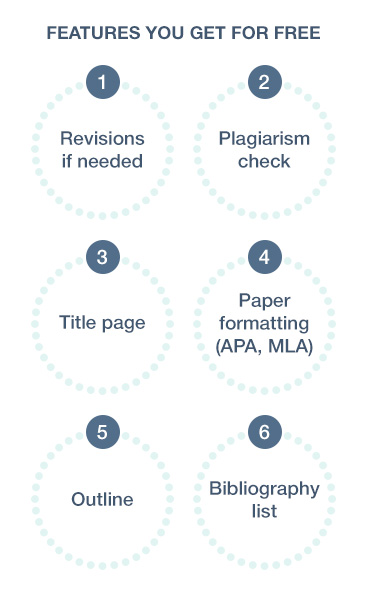

Get a Free Price Quote

Displaced Japanese agriculturalists first traveled to the sugar cane farms of Hawaii, with several migrating to California to labor in the citrus plantations and vegetable grounds. Originally, their numbers were comparatively small. Nevertheless, in 1894 when Takao Ozawa reached San Francisco, a few thousand Japanese immigrants were residing in the interior United States. The paper is about the history of Takao Ozawa, a Japanese immigrant who was determined to become an American citizen, and his contribution to America.

Japanese Immigration to the United States

Ozawa was born in the Kanagawa Prefecture on June 15, 1875. He was 19 years old when he came to California (Withington 4). Ozawa graduated from Berkeley High School in Berkeley, CA, and later attended the University of California at Berkeley for three years before he settled down in Hawaii in 1906 (Haney-Lopez 7). At that time, growing agribusiness firms initially welcomed the Japanese workforce. Besides, as the century turned, the Japanese were considered to be less socially and culturally hostile than the Chinese. The opinion of some white Americans was that the Chinese considered themselves provisional visitors instead of permanent inhabitants of the United States (Takaki 67). Generally, Americans did not regard the first wave of Japanese settlers in this manner. Japanese brought their families and new industries to America. Like Ozawa, several in the Issei community (first-generation) demonstrated an honest interest in structuring a permanent life in the United States, an interest that established itself in various assimilationist practices that Ozawa would personally invoke to define his association to American norms, values, and institutions (Withington 10).

According to Delgado and Stefancic (11), it was difficult to ascertain whether Ozawa experienced major racial hostility in San Francisco as he was not a farming laborer. Plantation work became a major site for white and Japanese racial conflicts. In 1902, Oxnard enterprise possessors formed a labor contracting firm the aim of which was to weaken the independent Japanese work contractors while simultaneously reducing labor costs (Withington 13). A year later, 500 Mexican and Japanese laborers planned the Japanese-Mexican Labor Association (JMLA) and steered 1,200 people to join demonstrations to demand that sovereign labor contractors be permitted to deal directly with manufacturers. J.M. Lizarras, the Mexican leader of JMLA, appealed to the American Federation of Labor (AFL) to approve his union, but AFL president Samuel Gompers agreed only on the condition that Japanese laborers be excepted from membership (Delgado and Stefancic 11).

In 1906, when Ozawa left California, people of Japanese origin became progressively susceptible to public attacks at the hands of white San Franciscans (Haney-Lopez 17). This increasing violence caught the attention of President Theodore Roosevelt, who organized a federal detective to San Francisco which found that the assaults were too recurrent to be understandable on the basis other than race.

If Ozawa did not recognize the formation of anti-Japanese thunderclouds in California, he would have been even more unprepared for the imminent racial tempest. For instance, the San Francisco School Board’s suggested isolating the fewer than 100 Japanese American learners it served and send the Japanese kids to “the Oriental school” (Withington 22).

Ozawa’s Contributions and Loyalty to America

Ozawa claimed that, in name, he was not an American, but at heart he was a true American. His account strategy defined associational and cultural practices that described his connection to the United States and his detachment from Japan (Delgado and Stefancic 24). Someone might question whether Ozawa’s self-representation mirrored his attempt to separate himself from the overall notion that people of Japanese lineage can never assimilate. Nevertheless, elsewhere in his transitory, Ozawa specifically disputed the impression that Japanese persons lacked the readiness and the capability to assimilate. Therefore, it is more accurate to say that, in recounting his family and social life, Ozawa sought to highlight his American identifications to reinforce his specific claim to American nationality, not to separate himself from or isolate other Japanese (Haney-Lopez 30).

Ozawa changed the political notion and definition of a true American citizen. He emphasized that a true citizen should not be a traitor, but should be loyal to the country. Contrary to General Benedict Arnold who was an American citizen, although a traitor at heart, Ozawa regarded himself as a loyalist and a “true American.” This contrast between “the true American” and “the traitor” became particularly noticeable in the context of political and juridical dissertations legitimizing the central government’s World War II internment of individuals of Japanese ancestry.

8 Reasons to choose us:

- 01. Only original papers

- 02. Any difficulty level

- 03. 300 words per page

- 04. BA, MA, and Ph.D writers

- 05. Generous discounts

- 06. On-time delivery

- 07. Direct communication with an assigned writer

- 08. VIP services

However, by the end of the first 10 years of the 20th century, the contradictions already had a significant social grip, making the Japanese look suspicious with regards to American loyalty (Haney-Lopez 44). Ozawa’s supplication of Benedict Arnold confronted this doubtful identity. His objective was not merely to progress an assertion that he had been and would remain loyal and patriotic to the United States, but also to make clear that he regarded it a part of his community responsibility to give back to the United States before he died. For Ozawa, the evidence of his identity as a “true American” was in his integration and, correlatively, his detachment from Japanese culture and institutions.

Ozawa made much of his expertise in English. Actually, one of his claims validating his qualifications to be a United States citizen was grounded on his articulacy in English. He reasoned that Section 8 of the naturalization act states that “no foreigners shall henceforth be accepted or admitted as a United States citizen who cannot be fluent in the English language, as long as the condition of this unit shall not apply to any foreigner who had, before the endorsement of this law, professed his plans to become a United States citizen” (Withington 50). Since Ozawa had professed such an intention, the English-language skillfulness test for naturalization did not apply to him. Therefore, he considered himself to have far surpassed this verge of being a citizen than obligated by law.

VIP Support Ensures

that your enquiries will be answered immediately by our Support Team. Extra attention is

guaranteed.

VIP Support Ensures

that your enquiries will be answered immediately by our Support Team. Extra attention is

guaranteed.

Also, Ozawa reformed the educational sector by inspiring the children of Japanese immigrants to attend American schools. He emphasized that he had educated himself in United States schools for almost eleven years and lived constantly within the US borders for over 28 years (Haney-Lopez 55).Throughout this period, he did not go to any Japanese schools nor did he associate with any official Japanese organizations. Actually, while the Japanese Consulate obliged all Japanese individuals to register with this agency, Ozawa declined to do so. He did not report his name, his marriage, or the names of his kids to the Japanese Consulate in Honolulu (Withington 56). However, these concerns were reported to the United States government, which, to Ozawa, was a vital signifier of his wider determination to integrate himself officially into American society.

Socially, Ozawa reformed the nation by living as a role model. The family life of Ozawa was organized around American culture and social standards. First, he chose a woman educated in the United States schools rather than one educated in Japan as his wife, one. This is mainly significant since between 1907 and 1923, 14,276 picture brides came to Hawaii from Japan (Delgado and Stefancic 70). Thus, Ozawa’s supplication of his spouse’s American education was a proof of her American socialization and also of his decision not to take part in picture bride marriages, a cultural practice that was common amongst the Japanese in Hawaii.

Become our VIP clients and enjoy these exclusive BENEFITS:

- 01 Paper delivery before the deadline

- 02 Free 1-page draft to each order

- 03 Extended revision period

- 04 Free plagiarism check

- 05 TOP 10 writers assigned to each order

- 06 Every order proofread by a TOP editor

- 07 VIP Support Service

- 08 SMS notification of the order status

Ozawa further emphasized that, mostly, he and his wife used the American language (English) at home. Consequently, Ozawa’s kids could not speak the Japanese language (Withington 90). As Ozawa’s daughter Edith Takeya describes, they did not have any Oriental friends as their neighbors were all Caucasian. Thus, Ozawa’s kids were thoroughly detached from the Japanese language and Japanese cultural organizations and friends (Haney-Lopez 77).Ozawa raised his kids in an English-only atmosphere.

With regard to religion, Ozawa changed the notion that Japanese immigrants could not attend American churches. Ozawa raised his children as Christians, taking them to an American church and an American institute rather than a Japanese one. Ozawa’s religious choices mirrored wider developments in the Japanese community as the majority of Issei were Buddhists (Withington 150). Indeed, a lot of the early Japanese-language institutes in Hawaii were Buddhist establishments.

Nevertheless, attendance at Buddhist pious services was scarce. Even though later efforts by Buddhist religious front-runners stimulated transformed interest in the open and active practice of Buddhism, this withdrawal from Buddhism reflected the era’s greater trend of Americanization in Hawaii to substitute old cultural beliefs with novel ones, which could be attributed to Ozawa’s efforts.

At least several Japanese institutions were openly loyal to westernization. For instance, the Japanese Association of America (JAA), which was formed in 1908, was an official agency that facilitated further ensuring that Japanese migration to the United States of America met the needs of the “Gentlemen’s Agreement” (Withington 188). As the main voice for the Japanese people, the organization needed to mold the perfect immigrant via a moral development campaign for the Issei. The campaign was more of a westernization project that aimed at the desertion of the “outdated” culture for a more contemporary aesthetic, including recommending that Japanese females in America wear Western feminine attire contrary to kimono and obi (Haney-Lopez 144). Ozawa was one of the supporters of the union and thus greatly contributed to social reform in America.

Also, Ozawa contributed to the economic reform in the United States by taking part in the JAA organization which embarked on an anti-gambling operation in 1912 (Withington 200). The alleged purpose of the campaign was to control the financial deficiency and the overall moral deterioration of those Japanese who took part in the kind of gaming provided by the Chinese. The grounds for ethical reform and modernization were embedded in the Japanese government’s wish to ascertain to the West that the Japanese community had the will and the ability to modernize.Ozawa’s venture in integration was not unexpected, since the Japanese government itself encouraged assimilation with the aid of Christian and Buddhist leaders (Delgado and Stefancic 204). Ozawa regarded himself as an image of modernity, and he freely placed himself in that role with the expectation that other people would as well see him that way.

Conclusion

In conclusion, regarding people of Japanese origin, historically both assimilation and modernity have been parts of the same broad field. It can be concluded that both Ozawa and the JAA were disputing Orientalism, although in their own ways. Indeed, Ozawa was a model of an integrated Japanese settler. Apparently, he had a genuine commitment to and investment in the United States socialization. Ozawa, in terms of his daily life, was already an American and a contemporary Western subject. In fact, Ozawa believed that he lived like an American. His profound faith was that the law would catch up with that realism in the end and officially legitimize it. Ozawa was humbly requesting for admission and acknowledgment as an American citizen. And, in order to do so, he used the assimilationist evidences of his own life, in which he upheld that they were absolutely true.